Are you really a customer's of choice?

Within the context of the current financial crisis, the importance of sustaining critical supply chain relationships has received more attention than ever. Despite the return to a “buyer’s market” in some sectors, the need to build and sustain supplier relationships is not obviated. Indeed, in an environment of heightened supply chain financial risks, supplier performance and reliability assume an even greater importance. Companies need to be “close” to their suppliers, to give them a clear understanding of how the ups and downs of the global economy will impact one another, and hopefully co-manage and preserve asset liquidity for both enterprises. This is difficult to achieve when suppliers view buyers as the “enemy”.

How do companies identify where they stand in the eyes of suppliers? And what are the characteristics of a “customer of choice”? While marketing specialists often use a “cost to serve” framework to define how suppliers view their customers, in reality there are a multitude of factors that shape these relationships. However, these factors, and the mechanisms and processes associated with building strong supplier relationships, are often unclear. People talk a lot about the value of trust in general terms, but less about the specific individual behaviours and operational issues that, added together over time, determine the level of trust between two companies.

To explore these issues, we conducted a research exercise among 100 suppliers to a major US grocery chain. As well as a quantitative survey, we also did one-to-one interviews with over 20 of these suppliers, which covered multiple categories. The results were summarised for the client’s supply management team in the form of a “customer of choice scorecard”, showing how the grocery chain was viewed by its suppliers along eight dimensions. Our analysis suggests that a fundamental shift in the supplier-facing organisational structure is an imperative in resolving some of the disparities and conflicts that exist today.

Attributes of customers of choice

There are multiple dimensions of performance that suppliers consider when working with customers. Next we will discuss, in no particular order, eight of the main ones that surfaced during our research.

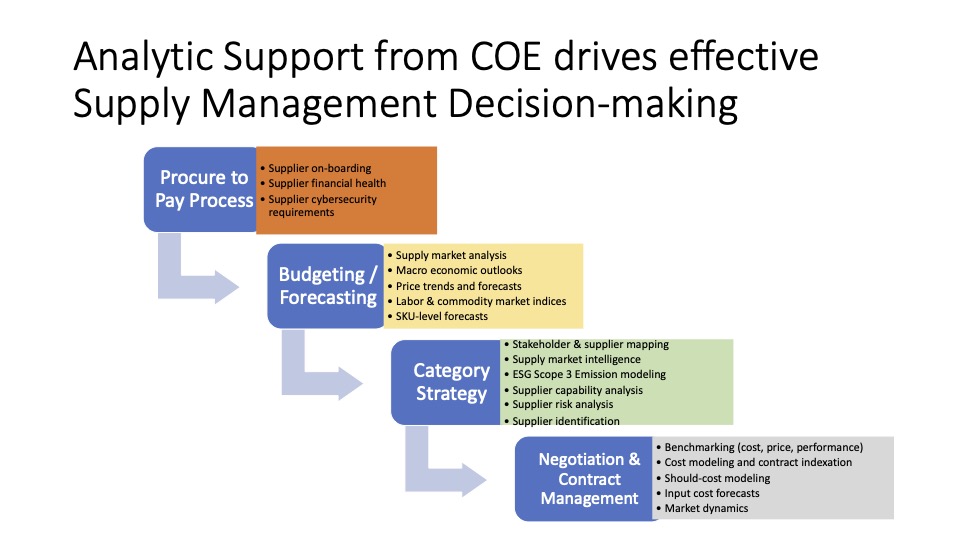

1. Accounts payable and the procure-to-pay cycle

Being paid in a reasonable amount of time is more important than ever in today’s financial situation and is one determinant of how attractive a customer is to do business with. Suppliers should also be able to work through a well-structured procure-to-pay process that avoids lengthy delays and delivers on-time payments. Many companies have payment terms of 60 days or more at the behest of their financial teams. But this cycle can be extended by inefficient payment systems, further delaying the timeliness of payments.

Analysis of the retail industry suggests that payment terms vary from as low as 20 days to as high as 60 days. The grocery chain we looked at had terms of 30 days, making it somewhat preferred. However, discussions with one of its suppliers revealed significant hold-ups and problems in communicating with accounts payable. “We have had a lot of money tied up with this customer,” it told us. “This is not good because the customer does not recognise their cost until it is approved in their system. We don’t invoice until we receive a service entry number back. If a service entry is not created in their system for an amount equal to or greater than our timesheet and we process our invoice, the invoice will be ’parked or blocked’. No notification is done to let us know that the invoice is not going to be paid.”

2. Ease of doing business

This category includes the experience of becoming a new supplier to a company – for example, going through the qualification process, obtaining insurance and getting its details on to the customer’s financial system. Once on board, an issue that often impact relationships is the point of interface; in other words, the different messages and degrees of co-ordination that a supplier may experience at different levels of the customer organisation.

One supplier noted that: “Corporate is very co-operative in working towards a win-win. I think site level is very difficult, as each store is its own fiefdom. There is lots of turnover and it is very hard to profitably keep relationships up. The demands put on new national suppliers are hard and not conclusive to a win-win relationship.”

3. Communication and supplier scorecards

Suppliers are often keen for face-to-face communication and feedback from customers. But our interviews suggest that most buyer-supplier communication takes place via e-mail rather than verbally. One reason is that the demands placed on sourcing co-ordinators and category managers are such that they have limited time to share information with suppliers and discuss product opportunities or sales strategies.

One buyer told us: “We are poor at communication with suppliers, but we only have so many hours in the day. I try to set aside one day a week for supplier meetings, although my schedule is often booked five or six months ahead. It is a sore spot with our vendors and a hard thing to manage, but often e-mail is the only mechanism we have available for communication, given my time constraints.”

Poor communication often means there isn’t a single voice to the supplier, which leads to conflicting messages about policies and performance. Scorecards are a good solution to this problem, as they can align expectations about performance, provide suppliers with objective feedback about how well they are performing and help to guide decisions about the allocation of future business. Our interviews revealed that suppliers prefer a clear system for communicating performance feedback, which can be used to focus on specific actions for improving the relationship.

4. Quality standards

Suppliers are often unfamiliar with stringent quality requirements that may exceed their capabilities, or simply are shut down because the requirements are poorly communicated or not communicated at all. There is an opportunity here to improve communication on quality standards earlier in the relationship, instead of at the last minute. For product suppliers, clear specifications, packaging requirements, pallet quality and delivery expectations provide important guidelines that they can build into their production systems from the outset, when the relationship is early in the development stage. Changing these requirements in mid-stream is generally more costly to the supplier, as the product may need to be scrapped or reworked.

Similarly, for service suppliers, specific guidelines as set forth in the statement of work, safety and environmental pre-requisites, levels of certification for critical employees and other expectations should be clearly expressed and communicated to suppliers prior to launch. Often, sourcing managers simply expect suppliers to read the fine print or, in a worst-case scenario, do not provide these details at all.

5. Contract terms and process

There is growing unease among suppliers we spoke to that although initial pricing discussions and contract negotiations were open, fact-based and fair, the follow-through on these agreements was not always well executed. Many suppliers expressed doubts about whether other stakeholders within the customer organisation accepted pricing and other contract terms. This is particularly challenging when a central strategy is developed with a global category team and the hand-off to business units is ineffectively communicated, resulting in lack of stakeholder engagement on the contractual commitments. Suppliers often terminate contracts with customers when business units engage in maverick buying and do not purchase minimum agreed volumes.

In terms of the end-to-end contracting process, rolling out products on a national or global basis is often poorly co-ordinated and not well communicated to suppliers upfront. One regional vendor told us: “I am thrilled to be in this position, but the win was a huge surprise as I did not know we were being considered for a national roll-out. I did not have much notice, only four to five weeks to pull together the necessary investment funds. It would help if the customer gave their vendors six months’ notice and a detailed list of what it is going to take so they are ready and have planned for when the national deal happens.”

6. Customer service

Major supply agreements should contain a customer service metric that assesses the extent to which the customer manages conflicts and resolves issues quickly and fairly. The cost to serve a customer, relative to the revenue and benefits received, is an important dimension of customer service. Generally speaking, suppliers value customers that are easy to serve and that only infrequently make last-minute changes to orders, requirements and forecasts that eat into suppliers’ margins.

When a conflict arises, there needs to be a defined process for getting these issues resolved, quickly and fairly. A single point of contact at the customer is an important element. This individual should be prepared to act as an advocate for the supplier and conduct internal investigations, since the problems may lie within the buying company as a result of poor communication of the type described above.

7. Forecast accuracy

Suppliers often suffer when forecasts are unreliable. Our research suggests that suppliers do not believe their customer forecasts, and often assume that the customer does not have a well-designed forecasting and category management process. This expectation stems partly from the lack of central co-ordination and partly from the inability of sites and regions to co-ordinate to develop a single forecast across lines of business that is meaningful for a supplier serving these regions.

Poor forecasts equate to poor planning on the part of suppliers, which is a circular process resulting in misaligned capacity management, product promotions and demand management. The application of collaborative forecasting has been documented for many years and can yield significant results in terms of improved co-ordination and alignment of joint goals and objectives that can benefit both parties.

8. New product introduction

Helping to build a supplier’s business and doing so in a partnership is at the root of becoming a customer of choice, especially for suppliers that are aligned in terms of culture, sustainability and values. But our research suggests that there is plenty of room for improvement in the introduction phase of new products and services.

One supplier we spoke to articulated this well: “I love the people at YYY – we have a similar culture. Our biggest frustration is the lack of organisation and decentralisation. We recently moved to a national programme and the experience was a nightmare; we almost regret going into it. We went in and set forth what we believed were the profiles we should go with based on our market data.

By conducting an in-depth look at how suppliers view your organization as a customer along these eight dimensions, companies can learn a lot about how to improve their relationship.