The Big Texas Chemical Freeze Raises Issues on Resiliency of the Petrochemical Supply Chain

Today’s Wall Street Journal article on the impact of the Texas winter storm on the petrochemical industry highlights many of the challenges that exist with this supply chain, that have been overlooked for too long. Christoper Matthews points out that a number of critical areas were impacted…

“The power outages brought the world’s largest petrochemical complex to a standstill, forcing more plants in the Gulf of Mexico region to shut down than during Hurricane Harvey in 2017. A month later, many remain offline, and analysts said it could be months more before all are fully back.”

Prices for polyethylene, polypropylene and other chemical compounds used to make auto parts, computers, and a vast array of plastic products, have reached their highest levels in years in the U.S. as supplies tighten. For example, prices for polyvinyl chloride, or PVC, have more than doubled since last summer, according to S&P Global Platts. The shortages in PVC and other materials are even shutting down automotive production lines, as well as other manufacturers that I’ve been speaking with. As plants slowly restart, it will take months for inventories to recover, with prices likely only returning to normal levels in June,” said Joel Morales, analyst at IHS Markit.

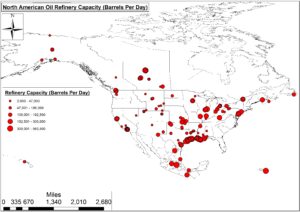

Discussions with experts on the Gulf Coast have also shared the challenges faced in this region. The delayed impacts of the petrochemical industry were urgent after the freeze. It is also testament to the fragility of this supply chain. This region endured two spikes of COVID and two tropical storms, all of which disrupted operations. This time, it took a whole week for recovery after the storm went through on a Sunday. This caused disruptions to multiple industries. Almost all packaging today is petroleum based, and in the lower 48 states, the bulk of refineries (which feed petrochemical plants) are in the Texas and Louisiana regions, (see map). This means that the majority of refining and petrochemical capacity is in a region susceptible to not only hurricanes, but also freezes like the one we had. This episode was a humbling experience, and, if variants in weather due to global warming continue to occur, companies need to look at alternative ways to manage their plastics and materials supply chains.

Discussions with experts on the Gulf Coast have also shared the challenges faced in this region. The delayed impacts of the petrochemical industry were urgent after the freeze. It is also testament to the fragility of this supply chain. This region endured two spikes of COVID and two tropical storms, all of which disrupted operations. This time, it took a whole week for recovery after the storm went through on a Sunday. This caused disruptions to multiple industries. Almost all packaging today is petroleum based, and in the lower 48 states, the bulk of refineries (which feed petrochemical plants) are in the Texas and Louisiana regions, (see map). This means that the majority of refining and petrochemical capacity is in a region susceptible to not only hurricanes, but also freezes like the one we had. This episode was a humbling experience, and, if variants in weather due to global warming continue to occur, companies need to look at alternative ways to manage their plastics and materials supply chains.

One of the big bottlenecks is nitrogen and refrigerants. There is only one manufacturer in North America capable of producing the high-grade ethylene required: Eastman Chemical (located in Texas). It is a major input into LNG and other refining facilities, and is only produced in three locations worldwide: Texas, China, and Korea. If it shuts down, most of the plants in this region would be impacted.

In another example, to get access to nitrogen, this company relied on shipping it in from Oklahoma, as the pipelines were non-functional. The truck took 6 days to make the normal 1-day travel time, due to road conditions. This required having 3 drivers on board to ensure that working hours were not violated!

As a result of this exposure, more companies are beginning to explore using biobased chemicals as alternative sources of supply. I am working on a study with the Green Chemistry and Commerce Council (GC3), and our initial research shows that this sector is growing rapidly. Using biobased feedstocks not only promotes a sustainability platform, but also provides alternatives to a supply chain that is susceptible to disruption. In the past, the cost of these biobased feedstocks has been greater than petrochemicals, which has slowed their adaption by industry. However, as prices have spiked with petrochemicals, and are unlikely to recover until the fourth quarter, this may be an ideal time to go green when it comes to plastics and chemicals.