Jason Miller Blog 2: Will Intel’s investments make a dent in our dependence on foreign semiconductors?

A great deal of hoopla is being made of Intel’s investments in its new $20 billion semiconductor chip plant near Columbus, Ohio, which Intel claims could expand into a $100 billion complex with eight fabrication plants. This is of course great news, and pundits are now proclaiming that this is the rise of the new “Silicon Heartland”. It is also an important first step as the Department of Defense and other industries have emphasized the importance of reducing our dependence on foreign semiconductors. In particular, with the majority of global production coming out of Taiwan (TSMC) and Korea (Samsung), the geopolitical risks of China and North Korea in these regions is no small worry.

We will need to be patient. Building a semiconductor plant takes more than 2 years on average, and often involves painstaking equipment installation, clean room validation, and lots of “copy exactly” procedures, (an Intel “mantra to do things exactly the same as you did it last time, because it works).

But just how big a dent will Intel’s investments make in our foreign dependence on semiconductors? To answer this question, my colleague Jason Miller at Michigan State University did a few calculations, and used bit of guess-work and a few assumptions, which gives us a pretty good idea.

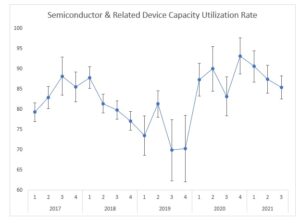

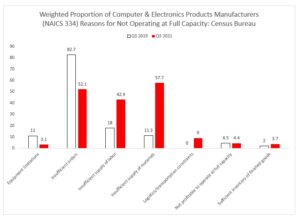

The first piece of data is the overall level of capacity utilization for semiconductor production in the United States. As shown in the graph below, it has hovered around 90-95% for most of 2020, and then dropped to 85% in 2020, likely due to worker shortages and COVID outbreaks. This can be interpreted as essentially “full capacity” – every operations person know that you can’t normally run a facility at more than 85%, especially with maintenance requirements, stoppages due to supply chain disruptions, material and labor shortages, and a host of other issues. We know this because the Census of Manufacturers tells us that the broader computer & electronics product manufacturing sector is itself being hammered by labor and parts shortages (see second graph). So this tells us that we are at full capacity already with our domestic producers.

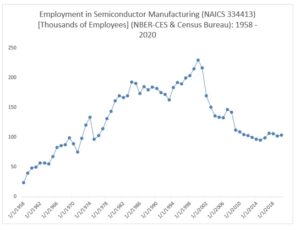

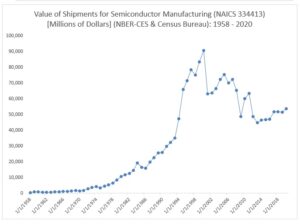

The National Bureau of Economic Research and the Center for Economic Studies partner to maintain a database containing 60 years of detailed manufacturing data (he merged this with the 2019 and 2020 Annual Surveys of Manufacturers (ASM serves as the basis for most years of the NBER-CES database, with years ending in 2 and 7 being the Economic Census). Employment in March 2020 was 103 thousand, down from 229.5 thousand in March 2020 (see the graph below). Likewise, nominal output in 2020 was $53.6 billion in 2020, down from $90.9 billion in 2000. For comparison, this means than Intel’s two new fabs outside of Columbus represent a ~3% increase in semiconductor employment (assumes that the complex will employ 3,000 people, as mentioned in the WSJ story).

Okay, so far so good. But what does this mean in terms of the contribution of these facilities to the demand for semiconductors in the United States. So the next bit will feature some speculation. From the 2017 Economic Census Jason pulled data on industry concentration in semiconductor manufacturing. This data shows the number of establishments operated by the 4, 8, 20, and 50 largest firms. Intel currently has 4 fabs in the US So figure there is a near 100% probability Intel’s plants are in the “4 largest firms” category. The employees per establishment seems reasonable. One can then estimate that the output per facility is ~$1.7 billion dollars per fab. Output in 2017 was $51.8 billion. Intel is promising this will be the largest fab complex it has when it is up and running, so let’s assume we are looking at an output of at least $2-3 billion for the new facilities. Putting this all together…..that would mean that Intel’s new facilities would constitute a 4-6% increase in US output.

At purchasers’ prices, total domestic demand for semiconductors in 2012 per the Detailed Use Table was $57.11 billion; we exported $27.3 billion, which brings us to the same value as the total product supply at producer prices. Using that figure of $57.11 billion in 2012 and assuming 2019 was the same, that puts 2021’s demand at ~$68.5 billion. $2 – 3 billion of production is certainly a start, but 4% of domestic demand is a drop in the bucket. In other words, we are still a long way off from being globally dependent on foreign semiconductor manufacturing. We need to begin finding ways to increase capital investments in new fab production in this country. It’s high time we become globally independent on a critical manufacturing resource that is required to take us into the digital age.