Blockchain pilots can support technology diffusion

I was a panelist on the Zycus / BG Webinar on AI in procurement today, and enjoyed speaking with Jon Hansen from Procurement Insights, Sally

Hughes from IACCM, and Jack Shaw from the American Blockchain Council. Although the discussion was primarily on application of AI in procurement, the discussion around blockchain also came out. It also triggered so

me thoughts, based on a conversation I had with a group of my MBA students, working with American Red Cross on thinking through applications for blockchain technology.

In a sense, all of these “hyped up” discussions of technology (block chain, AI, predictive analytics), are just that – discussions of technologies. Technologies are not good or bad, critical or useless, in and of themselves – but must be carefully thought through in terms of their application.

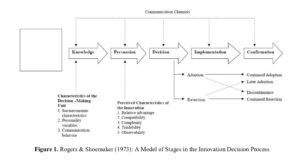

A good model for assessing the diffusion of technology that has been around for years, is one developed by Rogers and Shoemaker, on the Diffusion of Technology (1971). The authors, in their research, suggest that technologies are likely to be diffused more quickly, as a function of five major criteria: Relative Advantage, Compatability, Complexity, Trialability, and Observability.

There criteria are a very useful mechanism for executives to apply when considering whether to develop proof of concept investments in emerging technologies in the supply chain. In fact, I advocated to my students that this would be a useful approach to consider when advising any company on the application of blockchain to the business. I think the approach would be to identify specific business applications where the technology might be useful on the X-axis of a matrix, and the benefits / disadvantages of the technology on the Y-axis, and conduct a full assessment using the relative criteria. Such an assessment would help identify potential applications of block chain that would be the best candidate for a proof of concept. For example, consider the following criteria:

There criteria are a very useful mechanism for executives to apply when considering whether to develop proof of concept investments in emerging technologies in the supply chain. In fact, I advocated to my students that this would be a useful approach to consider when advising any company on the application of blockchain to the business. I think the approach would be to identify specific business applications where the technology might be useful on the X-axis of a matrix, and the benefits / disadvantages of the technology on the Y-axis, and conduct a full assessment using the relative criteria. Such an assessment would help identify potential applications of block chain that would be the best candidate for a proof of concept. For example, consider the following criteria:

Relative Advantage – refers to the advantages of the current technology relative to others. As noted in a recent Economist review of blockchain notes that there are several relative advantages that blockchain can provide, and that cryptography in general can provide. For instance, it may help to streamline supply chaoins, make dispute resolution easier when supply chains cross international boundaries, and provide a single distributed database for everyone use. This could replace the own proprietary systems that all parties in a chain might have, in different formats and different places, and perhaps could help streamline international payments. It might also be used to address potential counterfeiting. On the other hand, a major consideration that should be considered is the security of block chains. They can be hacked, like any other technology. And no one is claiming that block chains are more secure than any other procurement systems between partners in the supply chain. In fact, one block chain system, Ethereum has been hacked, and millions of dollars were lost.

Compatability – this refers the extent to which the technology is compatible with existing technologies. In a sense, this is a big question mark for block chain. The ideas around block chain are hardly new, as cryptographic linkages that secure entries in a block, known as Merkle trees, were first proposed in 1979. But experts also agree that companies will still need to resolve the same sorts of problems as for any other big IT project. So the barriers here are still present for adoption of any new IT innovation.

Complexity – refers to how complex the technology is to use by managers. Block chain is not all that complex – many providers have pilots they can demonstrate, and it is simply a function of programming on distributed ledgers, joined by a key. Pilots have focused on diamonds or luxury handbags, that already have certificates of authenticity, and block chains could potentially reassure buyers that those certificates are worth the paper they are printed on. But most buyers wouldn’t know how to employ block chain, so the mechanisms to use it would need to be simplified for the average person. In the procurement world, it is unclear how block chain systems would interact with existing procurement systems like Coupa, Ariba, and others that many companies have already invested in.

Trialability– refers to the extent to which the technology can be tested on a trial basis. To my knowledge, there aren’t a lot of block chain “trials” that people can go out and try for themselves. Although there are a plethora of companies that claim to provide access to block chains. In addition, David Gerard from the British Mecical Journal, noted that”Blockchains don’t solve the underlying problem of agreeing on what you want to do and how.” To develop a trial, there needs to be a specific application of how the technology will be used to solve a business problem or transaction. To address this requirement, block chain technology providers and consultants will need to work with companies to launch proof of concepts, to overcome the doubts that exist on how the technology will work.

Observability – refers to the extent to which others have successfully used the technology and can be observed as being successful. Block chain has very few observability opportunities for users to look at. There have been some discussions around how block chain could improve global logistics, and pilots with Walmart and Maersk that are underway. There has also been some initial pilots in the financial services sector that involves linking them to smart contracts. These pilots certainly have potential, but to make block chain really a technology in use, more use cases will be needed.

While the promise of blockchains in supply chains is clear, the likelihood of quick diffusion of the technology is low, base on the Rogers and Shoemaker criteria. To advance diffusion, providers of the technology, consultants, and organizations need to start to run pilots to advance each of these elements.