Recommendations to the US government for domestic alignment of supply chains in 2022

The lessons of 2020 and 2021 have led many organizations to begin questioning whether a domestic supply base is something that should be considered. The executives I’m speaking with are considering how to re-align their supply chains, and the word “risk” and “resilience” are a much more common part of their vocabulary. But moving forward with such an approach is tricky – and expensive.

Creating a globally independent US-based supply chain would entail development of a prioritization of critical supplies that are required for improved response in the case of continued COVID disruptions, trade flow disruptions, stay at home mandates, and on-going security concerns. Executives are beginning thus to consider development of policies for either development of a domestic capability, or a means for managing the supply of these items from global sources. As an example, individuals pointed to the fact that during COVID, domestic manufacturers sprung up to produce N95 masks, supported by DoD SBR grants. However, following COVID, many of these same mask manufacturers are declaring bankruptcy, as their price point is much higher than the raft of Chinese manufacturers that are selling to healthcare distributors and hospitals. This is leading us to the exact same condition we were in before.

To address this issue, one recommendation I am advocating would be to create government industrial policies that are targeted at supporting a domestic “stop gap” manufacturing capability. Secondly, partnerships should be developed with distributors to enable visibility into their inventory systems, and ensure they enter contracts which set aside inventory for government allocation under different conditions of duress. This will require a set of common data standards and a common architecture to create a dashboard and control tower.

In addition, a multi-agency materials inventory portfolio based on in-depth supply market analysis is needed. At a minimum, this should include specialists in the following categories: semiconductors, precious metals, electric vehicle batteries, medical supplies (PPE, gowns, gloves), medical devices, pharmaceuticals, plastics and resins, medical equipment, biologics, healthcare personnel, and respiratory products. This will require team of supply market analysts with special knowledge of these categories, that track the condition of critical supply markets for medical supplies, the supply risks within those markets, and acquisition strategies to manage the risks. Multi-tier supply chain mapping can provide clues as to critical points of risk that can “shut down” the US healthcare sector, based on multiple forms of risk assessment.

Because re-shoring all healthcare products is not practical or cost effective, we believe a federal office should also be responsible for developing a “make or buy” set of analyses that develops recommendations for investment in critical manufacturing infrastructure within the United States. This should be deployed in conditions of elevated market risk that creates extreme exposure to other countries where the bulk of manufactured supplies are produced. This might include critical pharmaceutical products and raw materials, as well as other critical materials deemed to be of strategic importance. A “cold eye” view of this capability should be conducted by such an agency to provide an impartial and objective assessment of the likelihood of success for re-shoring.

This is important, because there are infrastructural challenges with the idea of re-shoring manufacturing to the United States. Our discussions with manufacturing executives suggest that once an organization commits to outsourcing to third parties in low-cost countries, there is a minimum planning horizon of five years involved, as this requires supplier qualification, audits, start-up, quality certification, and on-going ramp-up. In many industries, sourcing executives have embedded their supply chains in Asian regions, noting that “…these jobs will never return to Western countries.” As an example, 80% of the world’s production of certain medical products are produced by four manufacturers in one province in China. To establish alternative sources that are competitive, qualified, and at-scale would cost much more than the 25% in tariffs companies are paying today in the U.S. to import from China.

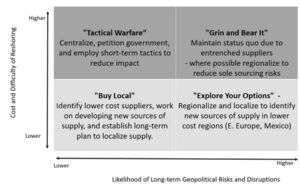

A group of researchers I’ve worked with in the UK developed a framework of supply chain strategies for geopolitical risk mitigation (see Figure below), which provides some guidelines to the federal supply chain on whether to adopt centralized/regionalized or localized supply chain designs according to how entrenched their suppliers are in a particular geographic location as well as how severe the geopolitical disruption is perceived to be.

Figure 1: Framework for Supply Chain Strategies for Geopolitical Risk Mitigation

The Y-axis of Figure 1 shows the shifts in the external business environment, which have rendered it difficult to localize or shift the supply base, because of the entrenched nature of the supply base, or the cost-prohibitive elements for doing so. We note here that many Chinese industries were established with government investment, and the cost of capital for developing local sources is a significant barrier for investing in local supply capacity. The X-axis refers to the perceived likelihood of on-going political risk and disruption that is likely to continue, including the likelihood of on-going tariffs, customs duties, quotas, and export restrictions, resulting from a major and ongoing geopolitical event such as Brexit or the US-China trade war.

Developing and exploring these strategic options is something that every organization should be considering right now. Because COVID isn’t going to go away. And who knows what in the future will replace it, when it comes to supply chain risks?